(Any views expressed in the below are the personal views of the author and should not form the basis for making investment decisions, nor be construed as a recommendation or advice to engage in investment transactions.)

Repeat after me …

“I Will not be exit liquidity!”

Being someone’s exit liquidity means you’re one of those schmucks who is buying or holding when the smart or connected folks are selling. In the context of this essay, exit liquidity refers to the unfortunate plebes who have been — and continue to be — on the losing side of the economic arrangement that is the US dollar’s reserve currency status.

The debate over whether the USD can be replaced as the global reserve currency is a heated one. On the one hand, some vocal elites of Pax Americana are incredulous that any country could step up to the plate and hold the world economy on its shoulders (America, Fuck Yeah!). On the other hand, there are increasing signs that certain corridors of trade are de-dollarising, and actually have been for some time.

Even the mighty French are tired of being America’s towel garçons and mademoiselles. French President Macron recently said that he believes his nation needs to reduce the “extraterritoriality of the US dollar.”

Reserve currency status comes with benefits, but it also foists certain costs upon the host nation. The primary benefit is clear — the host nation gets to print currency at will to pay for real goods. But that benefit is not distributed equally amongst the citizens of the empire. Though it has maintained its status as the wealthiest nation in the world, America’s levels of wealth inequality are currently among the worst in the developed world — and the situation continues to get worse and worse. The costs of being the reserve currency are felt acutely by the vast majority of the population that owns little to no financial assets. Below are a few distressing charts from Pew Research.

While even some former vampire squids are starting to acknowledge that the country’s role as the issuer of the global reserve currency is weakening the country overall, the most common retort to their concerns is, “well, who or what could possibly replace the dollar?” Many might erroneously suggest that China is itching to promote the CNY / Yuan / Renminbi as the dollar’s replacement, given that it’s the second largest economy globally. But, those who are sceptical that anyone besides the US can handle the gig will respond by trotting out some hard truths about the Chinese economy, including the fact that the country’s capital account is closed, and that the vast majority of trade is still priced in dollars — with no signs of slowing. “What can you buy with the Yuan?” those sceptics will ask.

This debate raises a few highly pertinent questions that deserve further exploration, including:

Is de-dollarisation actually underway, and to what extent?

Is the dollar’s role as the global reserve currency good for the majority of Americans at this particular time in history?

Does China actually want to be the issuer of the global reserve currency?

What currency or currencies will eventually replace the dollar, given that history has taught us that all empires come to an end eventually?

These questions are critical to predicting how financial policy around the globe might develop as the influence of Pax Americana continues its natural decline. You’ll be shocked to hear that I think crypto is a key part of the conversation, too — but more on that in a bit.

Forming a view on whether de-dollarisation is a thang is extremely important, as it should drive how you save your wealth. This is especially important if you are a citizen of the West. Even if your country issues its own form of fiat toilet paper, you are still an American vassal, courtesy of your flag’s military and economic alliances. Your capital is at risk of being expropriated as the American financial elites struggle to stay in power while their empire crumbles beneath them. Do you really want to fuck around and find out what a rabid dog will do when cornered? Are you going to let yourself become exit liquidity?

Maybe after reading this, you’ll think to yourself, “well, I’m actually a card-carrying member of the financial elite, so this doesn’t really apply to me. In fact, this arrangement will probably benefit me!” That might be the case in the short-term, but ask yourself this … would you want to be a noble in King Louis XVI’s court on the eve of the French Revolution? Does the political situation between the polarities of political power in America point to cohesion, or is there seething rage lurking just beneath the surface, ready to explode when handed the right match? Your meticulously coiffed head is probably feeling mighty heavy on those shoulders of yours, but don’t fret — I’m sure some righteous woke or proud boy warrior would happily remove it for you.

Before I get to the end game, though, it behoves us to understand the simple economics that underpin the ongoing discussions around de-dollarisation. Many people do not understand how the flows of capital and trade work, and thus are driven to the wrong conclusions. So bear with me, as I’m going to start by going deep on the fundamental economics that support my assertions. And if your TikTok-addled brain can’t focus for 30 minutes, I suggest you save yourself the trouble and just open up a new tab, Google “ChatGPT-4,” and ask our future AI overlords for a summary of this essay.

Mirror, Mirror on The Wall

A currency is said to be the global reserve currency when the majority of international trade is priced in said currency. To help us better understand the economic impacts of a global reserve currency, I am going to present a simplified global economy of two actors: the US (global reserve currency issuer and consumer of goods) and Asia (which is composed of China and Japan, who produce goods).

Europe, and specifically the UK, isn’t a part of the conversation because it destroyed itself over the course of two world wars (from 1914 to 1945). America picked up the pieces and quickly became the richest nation globally. It opened its markets and allowed countries outside of the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence to sell it stuff.

China and Japan (aka Asia) are lumped together because they both pursued the same mercantilist economic policies to achieve growth. Asia financially repressed savers so that heavy industry could get cheap capital to build manufacturing capabilities. Asia then undervalued its currencies vs. the USD and suppressed workers’ wages so that goods would be extremely cheap for Americans purchasing them with dollars. This strategy was easy for Asia to implement because, well — let’s just say that if you’re thinking about trying to start a workers’ union in China or Japan, I wouldn’t recommend the “fuck around and find out” approach. Following WW2, these policies made Asia so rich that it became the largest economy globally.

In this simple model, the US buys stuff from Asia in dollars. Asia uses those dollars to buy energy and raw materials from the rest of the world, so it can produce more stuff for the US. Asia now has a lot of excess dollars that it earned from selling stuff, and it can do two things with those dollars:

Option 1: Buy dollar-denominated assets.

Option 2: Sell dollars in exchange for local currencies and give some of the earnings back to workers in the form of higher wages.

Option 1 keeps Asia’s currencies undervalued from a purchasing power perspective and allows Asia to keep on making and selling cheap stuff. Option 2 is desirable for the workers in Asia, who would be able to consume more because they would have higher wages and/or could buy imported goods cheaper. But, Option 2 does not favour Asia’s large corporate industrialists, because if the prices of their goods approached American price levels — driven by increased labour costs and an appreciating exchange rate — then they would sell fewer goods.

The post-WW2 global economy would not be in its current shape (that is, with America running a trade and capital deficit vs. Asia) without the following being true:

1. America has an open capital account. That means anyone with dollars can buy assets inside America in any size they like. A foreigner can buy US-listed stocks, US-incorporated companies, US real estate, and US government debt. If this weren’t the case, Asia would have nowhere liquid enough to invest its large amount of dollar income. If Asia wasn’t allowed to invest its dollar income in the US, then Asia’s currencies would appreciate and wages would increase. That is just maths.

2. America has little to no tariffs on imported goods. No country practises truly free trade, but America has always made it a priority to offer as close to free trade as possible. Without little to no tariffs on Asian stuff, Asia would not have been able to sell things to Americans for cheaper than American companies could produce domestically.

As trade rose after WW2, Asia needed an increasing amount of dollars, irrespective of whether the domestic American economy required a larger money supply. The more stuff Asia sells, the more commodities it must buy (in USD). If America is unwilling to provide more dollars to the world through its banking system (e.g., via loans from its private sector banks), then the dollar skyrockets in value vs. all other currencies because there are not enough dollars around to facilitate the increased level of global trade. For those who are perennially short in dollars due to their USD borrowings, a supercharged dollar is the kiss of death.

This presents a very big recurring problem in American politics. Having the global reserve currency means that the Federal Reserve (Fed) and Treasury must print or provide dollars by whatever means necessary whenever the global economy demands them. However, increasing the amount of dollars globally can stoke the fires of inflation, which hurt voters domestically.

In whose interests do the domestically elected politicians typically act? The foreigners who need cheap and plentiful dollars, or the Joe-six packs who want a stronger dollar to repel the terrible effects of inflation? As much as the politicians want to help the average American, the health of the entire world’s economy — along with America’s desire to remain the global reserve currency issuer — typically take precedence. So, when asked, the dollars are almost always provided. And if not, a global financial crisis ensues.

To give two recent examples, consider the Mexican Peso Crisis of 1994 and the Asian Financial Crisis of 1998. In both circumstances, US banks that were flush with deposits — many of which were from foreigners with lots of dollar earnings — lent to foreign countries in order to earn more yield and fully deploy the insane amount of capital they had on deposit. The sheer volume of dollars that needed to find a home caused malinvestment abroad. But the music was playing, so err’body had to get up and two-step.

In both instances, the Fed started raising short-term rates because the US economy needed tighter monetary conditions domestically. The rise in rates caused the banks to slow down lending abroad. Many of these loans were of dubious quality, and without a continuous flow of cheap dollars from banks, the foreign borrowers became unable to service their debts. Trade faltered as companies who depended on this dollar funding started going bankrupt in Mexico and Asia, respectively. The banks had to recognise their bad loans, which put their solvency at risk.

The Fed and Treasury are now facing a hard decision. The domestic economy needed tighter money, but putting the American people first would also put US banks in harm’s way due to their international loan portfolios. Y’all already know what happens when financial policymakers face a choice between supporting the people or the banks, so you can guess the rest — the Fed and the Treasury eventually caved and lowered rates to bail out the US banking sector. Of course, there were some elected officials that hooted and hollered about how unfair it was to their constituents to bail out banks that gave bad loans to foreigners, but the American economic model necessitated this policy response.

American banks will always have a deposit base larger than the domestic lending opportunities because foreigners flood the banks with cash earned by selling stuff in dollars. Banks will always lend too aggressively and sacrifice tomorrow to boost earnings today. The Fed and Treasury will always bail out the banks because they must in order to prevent a financial crisis that makes the dollar more expensive and lowers its supply globally. When banks contract dollar lending en masse to repair their balance sheets, it removes dollar credit globally, which in turn pushes up the price of dollars and lowers their supply.

So, we just walked through the impact that the dollar’s role as the global reserve currency has on the American banking system. But what about American financial assets?

Asia doesn’t just deposit dollars with US banks. They also buy stocks, bonds, and property.

The wealthiest 10% of Americans own 90% of all stocks. The global reserve currency arrangement benefits them significantly. The Fed will never let the banking system go bust, which means it will always print money to fill holes bigger than Sam Bankman-Fried’s legal bills. This printed money causes financial asset prices to increase. The wealthy also benefit because foreigners provide constant buying pressure in the stock, bond, and property markets.

If the 10% benefits, what about the other 90% of Americans?

For-profit American companies must do everything they can to maximise revenue and minimise costs. For companies that make real stuff (as opposed to software), labour is one of their biggest costs. Sir Elon recently binned 75% of Twitter’s work force and the company’s software continued working. Imagine if General Motors fired a similar percentage of its staff. How many cars would make it off the factory floor?

But remember, this is America — so manufacturers have to find some way to keep juicing those margins. Wouldn’t it be great if American companies could relocate their factories outside of America to capitalise on cheap labour in Asia, which intentionally undervalues its currencies and suppresses the wages and negotiating power of its labour? And wouldn’t it be great if those companies could then produce all their products cheaper abroad, and then sell them back in America at a cheaper price with no import tariffs? Surprise, surprise — that’s exactly what happened. Corporate profit margins went up, and union membership declined in tandem with the decimation of the American manufacturing base.

Chart on the Effects of Globalisation

Global Trade and Services Volume (white)

S&P 500 Index (yellow)

Case Shiller US National Home Price Index (green)

Manufacturing Value Added as a % of US GDP (magenta)

As you can see from this chart, financial assets like stocks and property received a significant boost from globalisation. The more the world trades, the more dollars need to be recycled into the US. US labour did not receive the same benefits, though, as evidenced by the lone falling purple line, which represents the share of manufacturing value added as a % of US GDP. Basically, if you’re an American, you’re much better off learning financial engineering than how to engineer the actual making of goods.

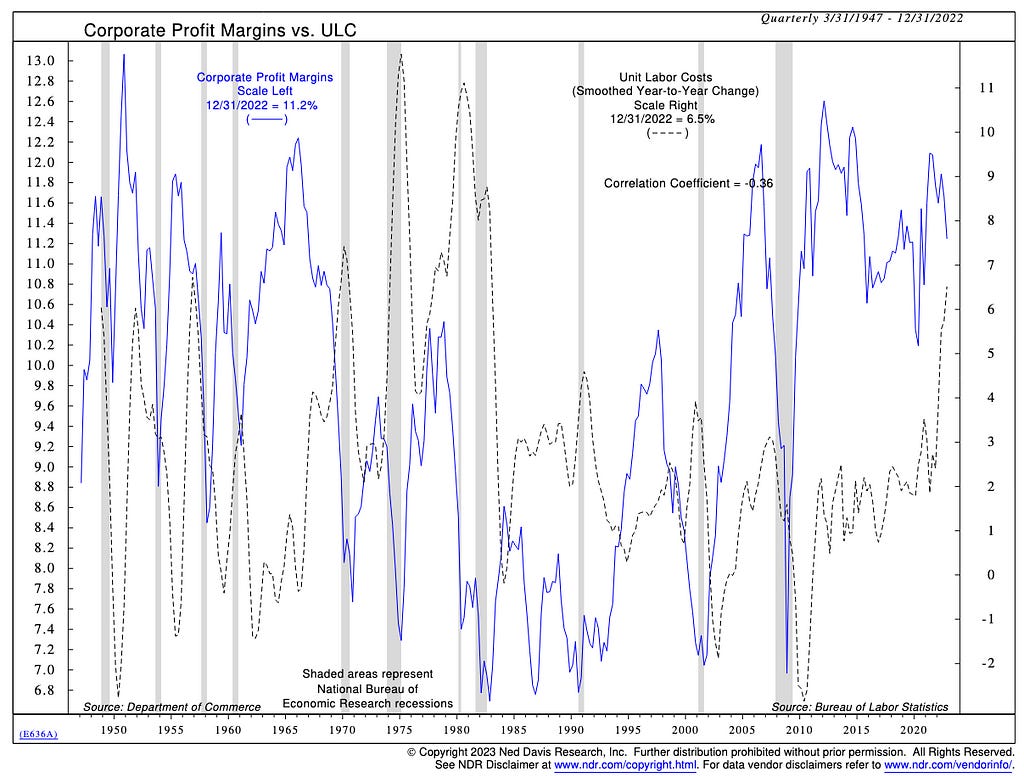

This historical chart from NDR clearly shows that US corporate profit margins are at the highest they have been since the 1950’s. However, in the 1950’s, the US was the world’s workshop (since everyone else was destitute after the ravages of WW2). In 2023, China occupies that role — and yet US companies are still enjoying profit margins that are similar to those experienced during the height of the US’ manufacturing prowess.

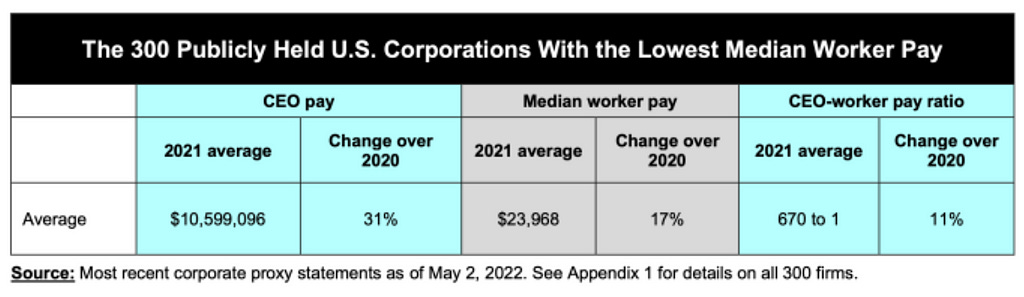

Corporate executives are rewarding themselves with generous stock options packages. These chieftains are also rewarding shareholders (which includes themselves) with stock buybacks and dividends, all the while decreasing CAPEX. This has resulted in CEOs making 670x more than the average worker, on average. Take a gander at the below charts for a fuller understanding of the pay distortion of American firms.

The good manufacturing jobs vanished, but hey — now you can drive an Uber, so no harm, no foul, right?! I’m being a bit flippant, but you get the point.

This outcome is guaranteed to continue — and likely worsen — so long as America continues to covet its role as the issuer of the global reserve currency. In order to maintain its seat on the currency throne, America must always treat capital better than labour. It must allow Asia to invest its dollars in financial assets. Capital invested in the stock market demands a return. And capital will demand that executives continue to raise profit margins by reducing costs. Reducing costs necessitates replacing expensive domestic labour with cheap foreign labour. If America does not treat capital this way, then there is no incentive for Asia to sell goods in dollars (since it wouldn’t be able to buy or invest in anything with those dollars).

If America resorted to pro-manufacturing mercantilist policies, then America / Asia trade would need to be conducted in a neutral reserve currency. And by neutral, I mean a currency that isn’t issued solely by one country. Gold is an example of a neutral reserve currency.

The current trade arrangement has benefited the financial elite who run America, but it has also been a boon to the general populations of Asia, who have been rebuilding their countries after a devastating global conflict. Which brings us to the next important question — is there any reason Asia would want to change this relationship?

Asia

In some respects, China and Japan have very similar cultures and economies. They are collectivist — i.e., the wellbeing of the community is considered more important than the individual’s. The stated goal of both Chairman Mao and the post-WW2 Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) that ran Japan was to rebuild their respective countries. The message to the plebes of both nations was essentially, “bust your ass, and we can get wealthy together as a country.” That is a gross oversimplification, but the end result was that these two countries became the 2nd and 3rd largest global economies in under a century.

These countries got rich, and the average Zhou / Watanabe enjoyed a much better standard of living than pre-WW2. Of course, labour in general did not receive the full benefit of the countries’ rising overall productivity, but again, the goal was never for the individual to flourish at the expense of the group.

So, as Asia looks at how far its current economic arrangement has gotten them, and then looks at the US’s precarious current position, they have to be asking themselves, “is being the reserve currency issuer even something we should be striving for?”

Does Asia want to have free trade?

No. Asia wants to raise the standard of living of its locals by selling stuff to rich Americans. It doesn’t want money flowing out of the region to purchase imports. The whole reason Asia got rich is that it restricted foreigners from selling things at an attractive price to locals. On paper, Asia is a member of the World Trade Organisation and is committed to free trade. In practice, there are a variety of ways in which Asia constrains the ability for foreign products to compete domestically on an equal playing field. America is perfectly happy to turn a blind eye to this, because the financial elites that control the country are the same cohort that own the companies that benefit from cheap goods and labour from abroad.

Is Asia for sale?

China’s capital account is closed. Foreigners are allowed to invest in a very limited subset of Chinese assets. There are specific quotas for the level of foreign ownership in the stock and bond market. Majority foreign ownership of most companies is not allowed. Even if you had a bunch of CNH (offshore Yuan or CNY), you couldn’t buy anything with it in size like you can in America.

Japan’s capital account is open — or at least, that’s what they claim. Japan has very polite ways of discouraging foreign ownership. Companies place a bigger emphasis on social stability — i.e., providing jobs for more people than they need — over turning a profit. There is also a high degree of cross-company ownership, which restricts the ability of minority investors to influence corporate direction. As a result, returns on Japanese equities are much lower than in the US.

As readers know, I love skiing in Japan. A foreign property owner there told me that during COVID, while the foreigners were away due to travel restrictions to enter Japan, one town passed a policy lowering the building density allowed on undeveloped land. This lower density regulation makes it practically impossible to build a hotel or large apartment block. This primarily impacts foreigners, who bought land in hopes of developing hotels and selling high-end condos. The locals will be perfectly happy if no additional visitors come and ruin their bucolic ski fields. There are more than enough hotel beds for the domestic Japanese visitor. Capital wants in, but society says no.

Bubble Gum

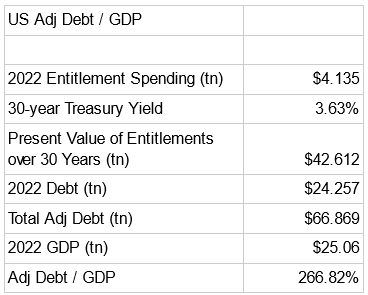

The US, China, and Japan are all grossly indebted. If you count the present value of future mandatory entitlements (US Social Security and Medicare), all three nations sport debt-to-GDP ratios of over 200%. The difference between the US and Asia is that a large part of US debt is owned by foreigners, whereas Asia is largely indebted to itself. This does not alter the likelihood that the debt will be repaid, but it does influence the speed at which the reckoning occurs.

When debt must be repaid quickly, a financial crisis ensues. If the debt is primarily concentrated at the sovereign level, this accelerated repayment of debt leads to outright default and regime change. You can look at the history of Argentina to better understand how this tends to play out politically.

China and Japan know they are overleveraged. However, because capital cannot come and go freely, the authorities have a lot of latitude in determining who bears the losses and how quickly those losses are realised. Japan experienced the severe bursting of a property and stock market bubble in 1989. The policy response was to financially repress savers using quantitative easing and yield curve control, and that remains Japan’s policy to this day. Its banking system and corporate sector has deleveraged over the past 30 years. There has been little to no growth over that time period, but there has been no social upheaval, either, because the costs of the bailout are being amortised over a longer period of time.

China’s property bubble has kind of burst. Real Chinese growth is likely between 0% to 2%, not the advertised 6% to 8%. The communist party is now undergoing the painful political process of assigning who bears the losses for a gargantuan amount of malinvestment and its associated debt. But, China is not going to have a financial crisis so severe that it shakes the people’s faith in the party and causes them to seek the overthrow of Xi Jinping. That’s because China will do the same as Japan and subject the population to decades of little to no growth and financial repression. They can do this because there is low foreign ownership of their debt, and capital cannot come and go freely from China.

Even after 30 years, Japan is still mired in debt. China tried to tame its property market, but the financial stress brought on by that policy proved too great to bear, forcing them to revert to their original plan of “extend and pretend.” Given the current state of both countries, Asia will not open its capital accounts and allow foreign hot money to come and go, since it would only serve to further destabilise China and Japan’s financial systems. Take note — trapped Asian capital is the exit liquidity that pays the price for over indebtedness (since it experiences financial repression and little to no growth).

A note about financial repression: I define financial repression as the inability to earn a rate on savings via government bonds that meets or exceeds the rate of nominal GDP growth. For example, if government bonds yield 3% but the economy is growing at 5% then savers are financially repressed to the tune of 2%. The citizens lose income that the government gains. And these gains are used to inflate away government debt.

Checklist

I confidently assert that Asia does not want to be the issuer of the global reserve currency. Asia is unwilling to accept the necessary pillars of a global reserve currency:

1. Asia does not want to allow foreigners to own any assets they wish in any size they like.

2. Asia does not want to disenfranchise labour to a significant extent vs. capital.

3. Asia wants to deleverage on their own time scale, which means foreigners cannot be allowed to own a large amount of government debt or other financial assets like in the US, nor will foreign capital be allowed to come and go as quickly as it pleases.

But just because Asia is unwilling to enact the policies needed for it to become the issuer of the global reserve currency, doesn’t necessarily mean that Asia wants to keep accumulating and trading dollars.

Regime Change

De-dollarisation is getting a lot of reps in the current conversation around the future of the global economic arrangement. However, the concept of de-dollarisation is not some new phenomenon. I have a couple of charts from Joe Kalish, the chief global macro strategist for Ned Davis Research, to illustrate my point.

Remember my simple global economic model: Asia earns dollars by selling stuff to America. Those dollars must be reinvested in a dollar-valued asset. US Treasuries are the largest and most liquid asset that Asia can invest in.

2008 was the apex of dollar hegemony. Right on schedule, the American banking sector spawned yet another global financial crisis. The response, as always, was for the Fed to print money to save the US dollar banking system. Holders of US Treasuries don’t like being shat on repeatedly. The amount of money printed in the ensuing decade was so egregious that holders of Treasury bonds started dumping en masse.

What did the producer countries start buying instead? Gold. This is an extremely important concept to understand, as it gives us a big clue as to what asset is most likely to dethrone the dollar as the future currency for settling trade and investment flows between countries.

Gold as a percentage of emerging market (EM) central bank holdings bottomed in 2008 — i.e., at the same time the dollar was at its mightiest. Following the financial crisis, the global South decided it had had enough of being exit liquidity for Pax Americana and started saving in gold rather than treasuries.

Together, these two charts clearly suggest that de-dollarisation began in 2008, not in 2023. Huh — now that I think about it, Lord Satoshi also published the Bitcoin whitepaper in 2008… what a coinkydink.

Understanding the top-level economic movements of the last 15 years allows us to understand why and how China and Japan changed their behaviour. When your entire economic model is predicated on selling stuff to — and investing the proceeds in — America, you lose financial independence. Like it or not, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) and Bank of Japan (BOJ) import the monetary policy of the Fed. That may seem bad enough on its own, but trillions of dollars of Asia’s wealth also depend on the good graces of American politicians. As Russia recently found out, rule of law and property rights are not ironclad.

I will focus this next part of my analysis on China, because Japan is a dutiful ally of the US. Just as one example, the US recently told Japan to increase their defence spending, and they obliged. Japan also hosts a large US military presence (even if the general population wishes the American GI’s would get the fuck out). As a result of this alliance, the BOJ and Ministry of Finance typically do what they are told when the Fed and/or US Treasury make strong suggestions about Japan’s monetary policy.

China, on the other hand, is in a bind. China still earns hundreds of billions of dollars per year exporting stuff to the US (and the world in general). China also holds trillions of dollars’ worth of US Treasuries and other dollar-denominated financial assets. Even though China owns a significant chunk of America, she is still listed as a strategic competitor of Pax Americana. But, China can’t just ditch the dollar, because China doesn’t want a bunch of foreigners flush with CNY to destabilise its financial system. Nor can it just market sell its treasuries, as it would get a terrible price for them.

As a result, China must work through a multi-step process to safely de-dollarise — not to replace the USD with the CNY as the global currency, but to simply lower its economic reliance on the US. The process goes something like this…

The first step is for China to start paying its major trading partners in CNY. As Saudi Arabia’s largest customer of oil, it makes sense for China to pay in CNY — and the same is true for all of its purchases from large energy exporters. If the energy input to the Chinese economy is priced in CNY, it requires China to “save” fewer dollars, which it previously used to buy energy. China has already begun to implement this step.

From there, the energy exporters can spend their CNY on Chinese manufactured goods. After almost 50 years of modernisation, China is the workshop of the world, and it produces just about everything a country might need.

If there is a large enough imbalance in trade between China and its trading partners, the difference can be settled in gold. China has a very liquid physical gold/CNY market located in Shanghai. If you don’t want to hold CNY, you can purchase gold futures contracts for physical delivery. This is super important because China allows the gold market to soak up any trade imbalances. If this gold link were absent, China would have to permit greater ownership of CNY denominated stocks and bonds. I explained earlier why China does not want to allow foreigners to own Chinese financial assets in size.

To further incentivise its largest trade partners to invoice in CNY when trading with China or Chinese companies, the PBOC will begin to aggressively roll out the e-RMB, a central bank digital currency (CDBC) that it has been testing since 2020. The e-RMB will allow instant, free, and zero-risk payments across the global South, which will replace the USD as the “hard” currency in places like Africa. Why fuck around with the intrusive banking system of your former colonial oppressors and slavers, when you can use a currency sponsored by a nation that just wants to trade and not get involved in your politics?

The goal of the e-RMB is to replace the USD in trade with China’s largest non-aligned trading partners. China doesn’t need or want to convince staunch US allies to drop their use of the dollar. China will still trade in dollars, but the size of China’s dollar earnings abroad will fall dramatically. With fewer dollars to invest, China can reduce the need to engage with the Western financial system. As China’s treasury holdings mature over time, China can sell these dollars and acquire gold. A recent disclosure points to an already steady rise in the official gold holdings of China.

Political Risk

One of the reasons investors previously favoured “developed markets” — and especially the US — was the absence of political risk. Political risk is the risk that when power shifts from one ruling party to another, the incoming party jails the opposition, and/or changes rules and regulations enacted by the previous regime just because they are of a different party. As an investor in countries with volatile politics, you can’t focus on the merits of one asset vs. another when your attention is fully centred on political power dynamics. Rather than engage in this risky exercise, investors instead chose to place their capital in an environment with a stable political arrangement. Previously, that was the US.

Power has seamlessly transferred between Democrats and Republicans since the end of the American Civil War in 1865. American presidents are no less crooked than any other heads of state — but for the sake of the system, the elites have managed to pass the baton between themselves without much in the way of sour grapes. Former President Richard Nixon was impeached for breaking laws while in office, and his replacement President Gerald Ford pardoned him.

For many years, capital has had nothing to worry about with regards to American politics. That has changed. Former President Trump was indicted by a court in New York City for a variety of alleged crimes. Trump might be a born-and-bred New Yorker, but the city has no love for him. Whether or not there is merit to his charges isn’t important. What’s important is that half the country voted for him, and the other half did not. A political flashpoint has been created that will be extremely divisive. Regardless of whether Trump wins or loses, half the country will be upset and believe the system is corrupt to its core.

2024 is an election year, and as you know, the number one job of any politician is to get re-elected. If you thought Trump owned the media airwaves before, then this public trial is only going to cement him further as a permanent fixture in the 24-hour news cycle for $free.99. News about this trial is everywhere. It doesn’t matter where you are in the world — the mass market news media are talking about this story. Politics is always about name recognition, so if Trump decides to run for president, it’s nearly a guarantee he will be the Republican party nominee.

President Biden’s house is made of glass as well. Allegations about shady dealings of his spawn Hunter Biden might lead one of Trump’s acolytes to indict Hunter for something. It doesn’t really matter for what — the narrative is that Hunter is crooked and his daddy is protecting him. Following such a move, each side would have the other’s king in check.

Again, the question (at least for those looking to trade on the future of American politics) isn’t whether Trump or Hunter is guilty or innocent. The question is, will the American public sit idly by and watch their hero be impaled by their political enemy? Will the 90% of America that has watched their good jobs go to Asia and their cost of living skyrocket be docile in the face of yet another affront? Or could this political instability be the match that ignites them to start asking the hard questions about why the wealth of Pax Americana hasn’t flowed to their household? Keep in mind that this is a relative discussion. It is not about whether Americans are richer on average than a family in Sub-Saharan Africa. It is a question about how a family in Flint, Michigan bathing in toxic water feels vs. a family in Manhattan that shops at Whole Foods.

Are the leaders of the Democratic and Republican parties concentrating on protecting their respective Lords, or investors’ capital?

As a steward of your capital, you must ask yourself — “do I want to continue to hold assets in a regime with these political and financial issues? Or would I rather ride it out in the (relative) safety of gold and or crypto?”

The Financial Balkans

The future will feature various currency blocs, but no global reserve currency hegemon. Trade with the West will continue in dollars, trade with the rest will be in CNY, gold, rupees, etc. When the blocs have imbalances between them, they will settle in a neutral reserve currency. Historically, that has been gold, and I don’t believe that will change. Gold is a great global trading currency if you can transport bulky, heavy items. Governments are good at these kinds of logistics — it’s a bit more difficult for the average person to lug their gold savings around.

As the global financial system balkanises, there will be less demand for US financial assets. Mohamed ain’t buyin’ no 57th street penthouse in NYC when he just saw how Yevgeny got his assets stolen for sporting the same passport as Putin, the “devil’ incarnate. The global South, which used to produce stuff to sell to the world in exchange for fiat toilet paper dollars, will begin accepting other currencies instead. Without the foreign demand for stocks and bonds at the margin, prices will fall. The biggest impact will be that, without a new bout of money printing, US bond yields will need to rise (remember: as bond prices fall, yields rise).

The West cannot allow general capital flight from its markets to places like crypto or foreign stock and bond markets. They need you, the reader, as exit liquidity. The colossal debts accumulated since WW2 must be paid, and it’s time for your capital to be eviscerated by inflation. A capital flight would also definitely spell the end for the USD’s role as the global reserve currency.

As I mentioned in Kaiseki, the West cannot easily enact draconian capital controls because an open capital account is a prerequisite for the type of capitalism it practises. Even so, if the West starts to sense that a mass exodus of capital is on the horizon, it will almost certainly make it more annoying and difficult to pull money out of the system. If you believe my thesis, then you should start to see many of the world powers’ recent financial policy changes in a different light.

The West is making it harder to buy crypto and store it in a private wallet. You can read about Operation Choke Point 2.0 and the Wall Street Journal to get a better understanding of this dynamic. President Biden’s administration keeps hinting that they may try to block US investors from investing in various sectors of China. Expect other such restrictions on investing abroad so that capital can stay at home and get disembowelled by persistently high inflation created by aggressive money printing.

Since 1971, investing in dollar assets has become such a no-brainer trade that many investors have forgotten how to actually do financial analysis. Moving forward, gold and crypto will be in focus. They are not tied to a particular country. They cannot be debased at will by a central bank desperate to prop up their financial system with printed fiat money. And finally, as countries start looking out for their own best interests rather than serving as slaves to the Western financial system, central banks of the global South will diversify how they save their international trade income. The first choice will be to increase gold allocations, which is already underway. And as Bitcoin continues to prove it is the hardest money ever created, I expect that more and more countries will at least start to consider whether it is a suitable savings vehicle alongside gold.

Do not let the financial media present this as an either/or decision between the dollar and the yuan. Do not let the lap dogs of the empire convince you that due to certain “deficiencies” in the Chinese economy, there is no currency ready to dethrone the mighty dollar. They are playing at misdirection — in the coming years, the world will conduct trade in a multitude of currencies, and then save when needed in gold, and maybe sometime in the near future, Bitcoin.